Newsletter: 13 Feb 2026

click here to sign up for our newsletter

Hello Readers,

While writing this newsletter, Kate (working remotely) asked Ross to send over a nice picture of the bookshop garden. He informed her that spring has not yet come to Swann’s Yard and to try again later, so instead, we’re offering you a nice list of books that you can curl up with until spring does its springing.

Our book groups are already in full swing this year, and after a slightly slow start to the year, we’re back to a stacked events programme in March, featuring several Irish events around St Patrick’s Day. You can find the full list here.

Best from the Five Leaves Team: Ross, Carl, Sarah, Giselle, Kate, Pippa, Deirdre, and Costanza

New From Five Leaves Publishing

________________________ |

We have two new books on our Publishing side this month. We’ve just received copies of from the printer of the much anticipated second volume of CJ DeBarra’s Queer Nottingham. This one covers the 1990’s to 2020, where we dive into the underground queer spaces of the hedonistic 1990s, then see the return to grassroots activism, and ultimately end up with our vibrant, diverse community, which plays such a vital role in Nottingham’s culture today. The book incorporates archival research with an impressive 175 interviews from people across the queer spectrum. Look out for details of an official launch party. It will be tough to out-do the event we had at Nottingham Central Library for the last volume, but we’re going to give it a go. | |

|

Due in any day now is the latest instalment in our D.H. Lawrence series with D.H. Lawrence and the Gypsies, by John Pateman. This one is an exploration of Lawrence’s lifelong fascination and affinity with people who lived outside the bounds of ‘civilised society.’ The book explores Lawrence’s intimate understanding of Romany culture, his admiration and longing for an itinerant life on the road, but also his reproduction of some of the stereotypes, and his exploration of class and race in the early 20th century. Author John Pateman describes himself as a “Gypsy, Librarian, Communist,” and we’re proud to call him a friend of the shop, as well as the author of Willie Hopkin: D.H. Lawrence’s Socialist Friend, which we published in 2024. | |

|

Just going into final edits now, is Devils in the Details, our second book with Rory Waterman and the Lincolnshire Folktales Project. Last year Rory was a co-editior of and contributor to our compilation Lincolnshire Folk Tales Reimagined. This time he invites us to join him on his travels around the county, in search of its folk tales through the landscape, architecture and history. Although this solo-authored book is about the folk tales, rather than focusing on retellings, it’s punctuated with weird and wonderful tales throughout, that will appeal to storytellers and story lovers alike. |

What We’ve Been Reading

_______________ |

__ |

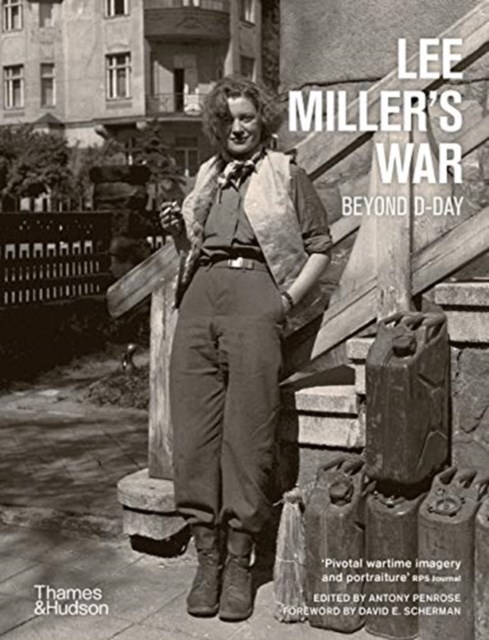

Lee Miller’s War: beyond D-Day edited by Antony Penrose (Thames and Hudson, £17.99)Having seen the film Lee, watched an online talk on her and attended the Lee Miller exhibition at Tate Britain, I thought it was time to pick up a book, or one book from among the many. Though the exhibition (open until 15th February) featured many aspects of Miller’s life ranging from her photos of fellow surrealists through to her pictures of North Africa, it was the wartime and post-war images that stuck with me, hence choosing this book. It’s illustrated by many of the best – in other words, most tragic – images but there are also many articles by her about her journey with troops, often on the front line as the Allies fought their way through France and Germany. Miller was among the first to photograph the invasion, the camps found by troops, and there’s even a photo of her having a bath, in Hitler’s bath, with her filthy boots on the bath mat in a chapter starting “I was living in Hitler’s private apartment in Munich when his death was announced”. –Ross |

|

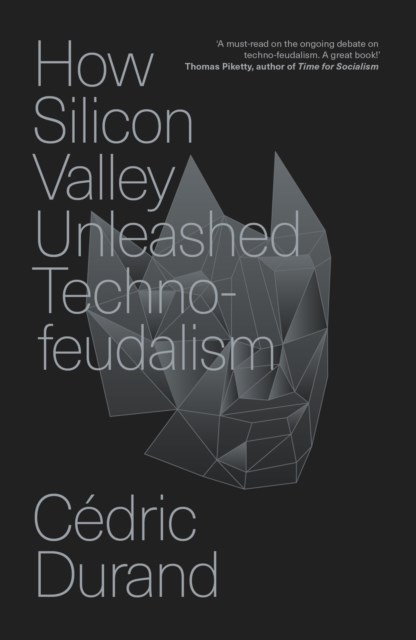

How Silicon Valley Unleashed Technofeaudalism: The Making of the Digital Economy by Cedric Durand (Verso, £12.99)*A provocative, political and economic critique of the digital economy’s dominant forces. Rather than ushering in a new era of innovation and prosperity, the tech giants have regressed toward a feudal order, where a few major platforms extract value and control data, turning users, workers, and even other businesses into dependent subjects, akin to feudal lords extracting rent and reinforcing dependencies rather than fostering competitive markets. –Carl*unavailable on our website at time of mailing email us to reserve your copy |

|

|

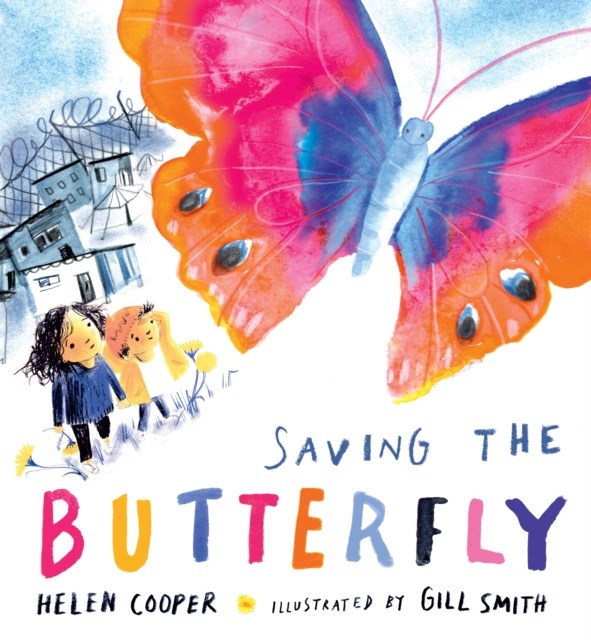

Saving the Butterfly : A story about refugees by Helen Cooper illustrations by Gill Smith (Walker, £12.99)When two refugee children try to remake their lives in a new home, the younger one is able to start over, but the older one’s anxiety keeps her hiding in the house. One day the younger one brings her a butterfly, but it can’t live its whole life stuck inside. It’s up to the older one to rescue it, but to do that, she’ll have to go out into the world. A touching story with beautiful art which addresses both the refugee crisis and the topic of children’s anxiety with a gentle hand. –Kate |

|

|

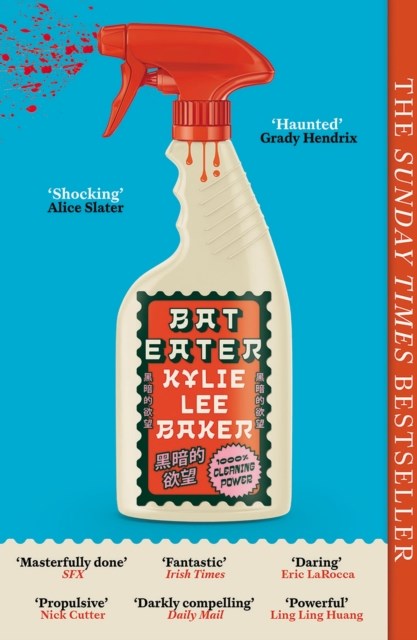

Bat Eater by Kylie Lee Baker (Hodder & Stoughton, £10.99)This was the first book I finished in 2026 and I haven’t stopped thinking about it. It’s also the first squarely “Covid novel” I’ve read, and I realise I’ve been avoiding books directly engaging with an ongoing pandemic we are not done experiencing let alone processing. However, this is filled with a rage it turns out I needed. It is gory and visceral and definitely not for the faint-hearted! The book starts with our protagonist, Cora, witnessing her sister’s death and follows her trying to navigate that loss alongside experiencing anti-Asian hate, a possible serial killer, hungry ghosts and messy family dynamics. The book grapples with mental health, the migrant experience and trying to belong, all while being a propulsive, compelling read. I couldn’t put it down. –Sarah |

|

|

Things That Disappear: reflections and memories, by Jenny Erpenbeck (Granta, £12.99)Jenny Erpenbeck won the International Booker Prize for Kairos, a novel of coercive control set in Berlin as her native East Germany moved towards the endgame. So much of her work relates to that disappearance, as do some of the essays, all short, in this slim volume quite suitable for a train journey to London. All the essays appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and are translated here by Kurt Beals. Some of the disappearances are very personal, of loss, some of just parts of life that have moved on or from which you have moved on. I imagine that most of the readers will be Erpenbeck readers, but there are a lot of them around. –Ross |

|

|

This, My Second Life by Patrick Charnley (Hutchinson Heinemann, £16.99)A quietly restorative and beautifully written literary debut follows a young Jago Trevarno as he rebuilds his life after surviving a cardiac arrest that leaves him with lasting brain injury. Relocating to his uncle’s farm in rural Cornwall, his days are measured by the rhythms of nature and the simple tasks of farm life. His fragile stability is tested both by the return of his first love and by growing tensions with a local landowner, lending a subtle narrative tension (what is behind that locked door?) to the reflective tone. A perfect fiction pick for the winter’s end / early spring transition. –Carl |

|

|

Gliff, a dystopian novel by Ali Smith (Penguin, £9.99)This doesn’t work for me as a novel, but it’s still worth reading. Gliff is a horse, bought, though not actually paid for, by two children who have fallen outside the system when their house is marked for demolition and they have to look after themselves. Their mother is working in a hotel somewhere and an older youth gives them some money, finds a temporary place for them and disappears from the scene. The hotel says they have no record of their mother. Data is all. The book hints at so many bad issues we have to deal with and is prescient about new issues that have come up since she wrote the book. The demolished houses, for example, first have red paint daubed round them and people feel uncomfortable near them. Flags, anyone? The right of residence can be taken away easily. ICE? –Ross |